Yue, Naomi and Polina from Nomaos Collective about What Do Landscapes Say?

Nomaos is a cross-disciplinary collective of Russian and Dutch makers and designers. Their research project ‘What Do Landscapes Say?’ investigates the diversity of and relationships between landscapes and identities in Russia. Daria spoke to Yue Mao and Polina Veidenbakh, initiators of the project from the Dutch and Russian sides, and curator Naomi van Dijck, to discuss what unites their team, how they've formed their particular speculative artistic approach to the landscape, what the cross-disciplinary and cross-cultural exchange had taught them, and how they try to address current ecological problems.

Nomaos collective. What had brought you together? Who was the initiator?

Yue: My research and interest in the topic of landscape started after my graduation. I saw the open call from the Creative Industries Funds Netherlands. They were looking for cultural projects which foster inclusive cities and societies through design. The particular focus was on Russia, Egypt, Turkey, and Morocco. And I thought that urbanism and artistic research were a good match. I contacted the artists I knew and whose practices were related to this topic and asked them to participate. In parallel, I searched online for artists and designers from Russia : this is how I met Polina. Gradually, the collective formed itself, with people with very different backgrounds and experiences : architects, urbanists, visual artists... We believe that various media give us a different perspective and lens to present the topic. Some of us focus on drawing and illustrations, others on video essays, graphic design, and writing.

How many participants are in your group? Can you tell us more about your profiles, backgrounds, and what triggered your interest in the topic of the landscape?

Yue There are ten participants for the Rotterdam exhibition and eight for the Moscow exhibition. About the background, I studied urbanism. During my studies, I understood that there is a human-centered approach in the urbanism field and that all design projects are too focused on humans and their needs. At some point, I got curious about the areas where natural forces are stronger than human ones, and how these forces are shaping us and our practices. This is why I got interested in the topic of the landscape. Later, I participated in a research project about indigenous Arctic landscapes and related lifestyles. Through this research, I figured out how our experience shapes our approach to the landscape from the position of the architecture and the way urban design approaches the topic of relationship with nature.

Polina I am an architect who got involved in the field of urban design. I think that Russia has been a kind of playground for urban designers since the revolution of the early 20th century. Many bold urban ideas were brought into reality here. But there were different moments. For example, during the Khrushchev era, standardised concrete buildings were simply copy-pasted all over the Soviet Union. Urban designers of that time just followed the manuals of 20th-century urbanists, thinking that they were improving the human environment and that they were right about it. But in reality, it was quite the opposite : they were missing the whole point of working with identities. In modern urban practice, people use a lot of tools from the past. Therefore, for me, it is interesting to work with identities. I took part in many different workshops and research programs in Europe to explore this topic. With the Landscape project, I was interested in the development of different urban tools. More than just data, I tried to use more sensitive data, like artistic data, which helps to investigate the landscape. So when we formed the team, it was crucial for me to work with people who are familiar with these types of artistic tools.

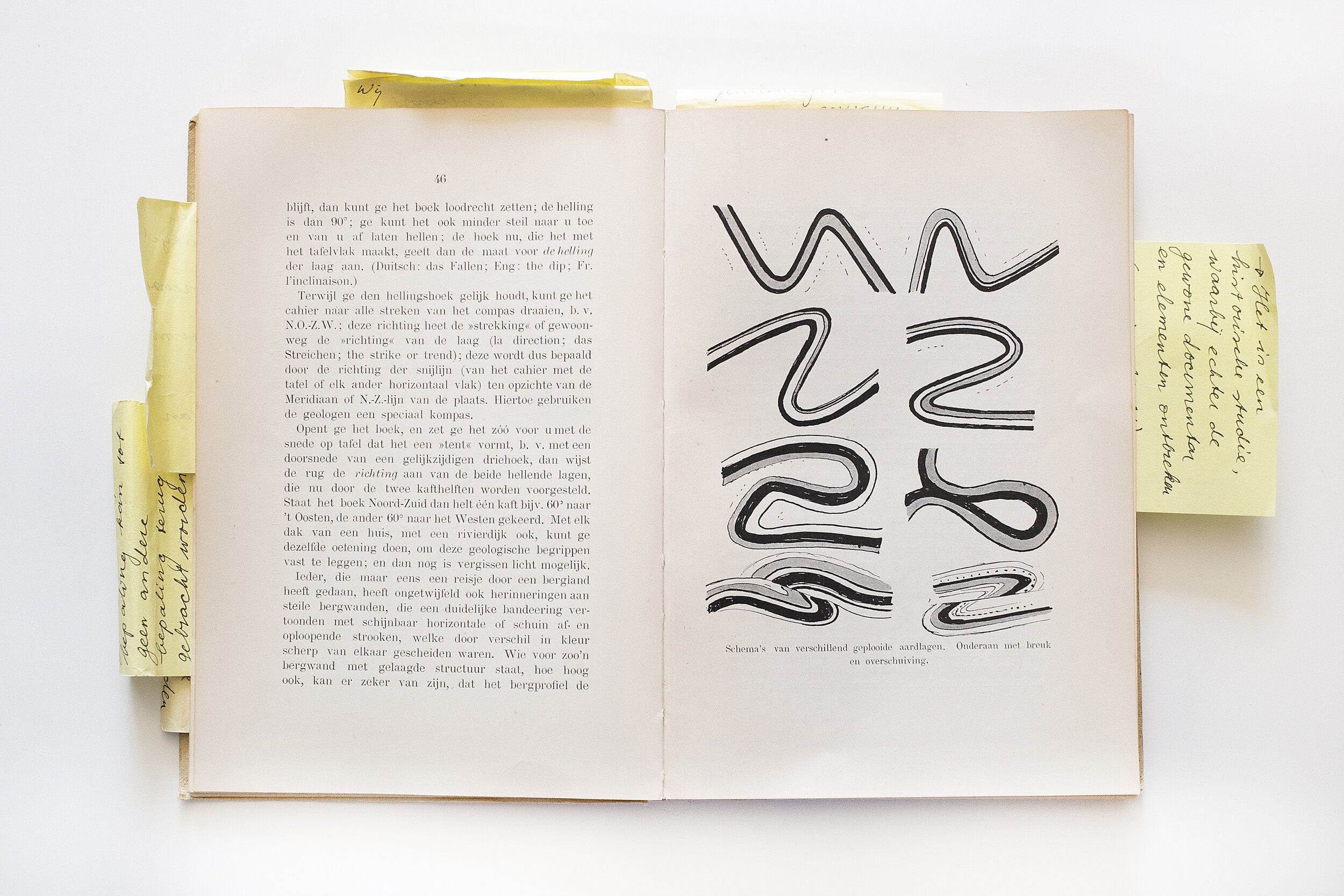

Credit : Jhoeko

Naomi Initially, I was just an adviser on this project, and only then took on more responsibilities as curator. I have a conceptual interest in landscape, based on its diversity, and what it can teach us about ourselves. For the Nomaos artists, the connection with nature meant they would ask questions about each place and the way we are perceived as a part of these places. Is there a reason to separate us - human - from them - landscapes ? How has the way we have acted upon nature influenced us? In the project, some artists look more into the topic of nature preservation - others work more on sociological backgrounds.

About how we treat the landscape around us, do you feel any social responsibility? Did this project aim to draw people’s attention on the current ecological problems?

Yue Ecological problems are a big part of our project. All projects from the collective are somehow related to it and address a much broader context around it as well. For example, some projects were created to build a stronger local engagement on environmental topics. Everyone among us had a very different approach, but what brought us together in the first place is that we all recognise the exploitative approach to the landscape that we see nowadays. Rachel’s project directly deals with mining and the ecological crisis. Her project is probably the most direct and radical. In general, we have tried to use the soft power of the narrative to address this topic by helping the audience to feel more connected with landscape. The project stimulates people to reflect on the connection they have with nature, or maybe the one they lost.

Naomi Also, if we talk about the ecological crisis, we address a much bigger issue than individual scale. To circumscribe it, we talk with numbers : reduction rates and other indicators. All of them are quite abstract and do not really allow us to react. What we have tried to do is to zoom in and see where we can find an overlapping interaction between us and nature on a small scale. What can the way we nurture our gardens say about a larger-scale approach to the landscape that we have?

Credit : Nataly Lakhtina

Your approach somehow makes me think about the theory of hyperobjects that Tim Morton has developed. Our relationship with nature is something too big to understand in a full sense.

Naomi You are partly right, but as a theoretical background, I rely on the 'contaminated diversity' theory by Anna Tsing. She highlighted the cultural and biological ways of life that have developed during the last few hundred years of widespread human disturbance and adaptation of our ecosystems to it.

The project is full of very different creative forms, including installations, films, illustrations, and creative writing… What common narrative connects them ? And which curatorial decisions did you take to highlight it?

Naomi This was quite a complex thing. Due to the COVID situation, a lot of projects had to evolve. This situation added a lot of confusion into the organisational process. We had to take a step back and reflect on what we could do with the projects where people were supposed to travel for their research. In the very beginning, the group of artists was not united by a common idea. So, as a curator, I tried to delve into each participant’s approach and project to understand what collective meaning could emerge. An in-deep interview with every participant was a helpful tool to create a narrative. It was pretty interesting to work on the group dynamic. At the same time, each participant’s individual practices were respected. We shared our thoughts with each other during the whole research process by organising common discussions. To create a dialogue, I proposed a vector and a common narrative, taking into account the ideas of all participants.

Initially, every participant planned to address the identity of a specific location in Russia. Russia is the biggest country in the world with a huge variety of climate zones: how did you identify research areas ?

Polina When planning our trip to Russia together with Yue, it was indeed a really tough decision to choose the areas. As you said, Russia is a huge country, and there are a lot of beautiful places to visit. So we decided to concentrate on Western Russia. To show variety, we chose places like Karelia and towns around, Kizhi island, touristic Saint Petersburg, and Vyborg, a border city where you can find a mix of Russian, Finnish and Swedish cultures. We tried to give a small overview of what you can find in Russia. There are amazing landscapes, cities, and the way people interact with them was a matter of interest. This was a basis but artists were free to choose where they wanted to go and what they wanted to focus on. We wanted to highlight more the depth than the broadness of the exploring context. After the field research (which was shortened due to Covid), a huge part of our work was to dive in the material we collected. The output is some kind of accumulation of our experience on the field and the perception of the landscape that came from it.

I guess the COVID pandemic influenced your research tremendously. How did you adapt to the obstacles, and how the project had changed because of it?

Yue Fortunately, all the Russian team had managed to achieve their research projects, while the team from the Netherlands faced a lot of difficulties due to travel restrictions. Due to this, a lot of projects were adapted into a digital format. Many participants are still planning to finish their research and visit Russia when the situation with the pandemic will be better. For now, we don't have clear plans for the future, but the project will continue to exist as a developing archive for at least two years.

Besides being a cross-cultural project, ‘What Do Landscapes Say?’ is a good example of a cross-disciplinary exchange. How did this affect your collaboration?

Yue For me, it was indeed fruitful collaboration, probably because we are all from different parts of the globe. I felt quite familiar with many aspects when I work with Russia context, also concerning some political issues. For example, once I did not agree about the vision of the inclusiveness topic. Inclusiveness in the sense that something is included in something was strange to me. My understanding, which is not typical for Western Europe, was that inclusiveness is perceived as community specific and pretty natural. Therefore, I tried to present the topic of the landscape and identities in Russia without judgment. In the end, the project is way more about diversity rather than about inclusiveness. As a person from China living in the Netherlands, I think I have more sensitivity to this topic. Actually, I have been kind of experimenting by choosing to use the concept of inclusiveness in a way which is not spontaneous for me.

Naomi I am Dutch, but I live and work in the UK. Living and working somewhere else teaches you strangely so much about your own country. The Netherlands can be quite self-proclaimed in a way they design their cultural strategies. And as Yue said, the inclusivity topic is a good example of it. What I have learned from this group, is that everybody has their form of radicalism. And these borders should be respected. For example, here in the UK, the topic of political responsibilities seems more sharp. In the Anglo-Saxon environment, if you are not politically active, what are you doing? I don't think that we can apply the same approach to all contexts.

How has your perception of landscapes changed after the project?

Polina I believe that the turning point for the Dutch group in the understanding of how huge Russia is were our trips across Karelia. It took around five hours during daytime. I visited the Netherlands a couple of years ago, where I lived in a tiny city in the north of the country. Everything could be reached in 10 minutes by bike, while Russia is so huge, and sometimes you feel like it is not adapted for humans at all. Together with Naomi, we discussed our approach towards the landscape and similarities between our countries a lot. I think the Russian team learned about our landscape from and through the experience of the Dutch group. This group experience gave me another approach and understanding of the landscape. I feel that there was an issue related to the way the Dutch side perceived information during our trips. Of course, we were trying to be as critical and objective as possible while delivering it, but in many ways, it reminded us of the touristic experience, rather than a research experience. Unfortunately, it is still hard to travel in Russia due to infrastructure.

Naomi The landscape in the Netherlands is very controlled by the government. Recently, many new restrictions were implemented on new buildings due to the pollution level. What was interesting with our project is that it revealed a top-down situation: in Russia, there is so much free land that the government cannot decide what to do with it, whereas for us, because there is not that much land, the government has to decide what to do with it.

Recently you have opened an exhibition in Het Nieuwe Instituut Rotterdam in Rotterdam. Can you share your emotions from it?

Naomi Well, first of all, just half of the team was able to be on site, so we faced some difficulties in the montage stage. It is always hard to montage the work of an artist without them being there. Initially, we planned a lot of parallel activities such as workshops, but unfortunately, due to COVID, we had to adjust things to an online format. We had an online panel discussion on our Facebook page, where we discussed the background of the exhibition. Every week we are publishing additional materials on our website, such as podcasts, workbooks, which allow us to enrich the audience experience.

Starting on October 15th, another exhibition will open in the gallery Na Peschanoy in Moscow. Why did you choose this gallery? And which expectations do you have from it?

Polina It was quite hard to find a gallery that would be ready to host us, given that we are quite a big group, and the exhibition calendar is busy for many years for many galleries. It was pleasing that the gallery helped us to present the project from the perspective of its unique variety of media and different points of view.

Naomi I was impressed by their engagement program. The gallery focuses a lot on building a relationship with local communities. So it was great to work with an institution that shares the same philosophy. I think, in the end, we had got an interesting cross-disciplinary project altogether.

Curator: Naomi van Dijck, Curatorial assistant: Yue Mao

Producer: Naomi van Dijck, Yue Mao, Polina Veidenbakh

Exhibition designer: Polina Veidenbakh (Moscow), Maria Kremer (Rotterdam)

Graphic designer: Maria Malkova, Vika Nurislamova, Daria Nikulina

Contributing artists:

Rachel Bacon, Ksenia Kopalova, Nataly Lakhtina, Maria Malkova, Yue Mao, Vera Mennens, Radha Smith, Polina Veidenbakh

Fore more information, head to the collective website, Facebook page, or the Na Peschanoy Gallery website.